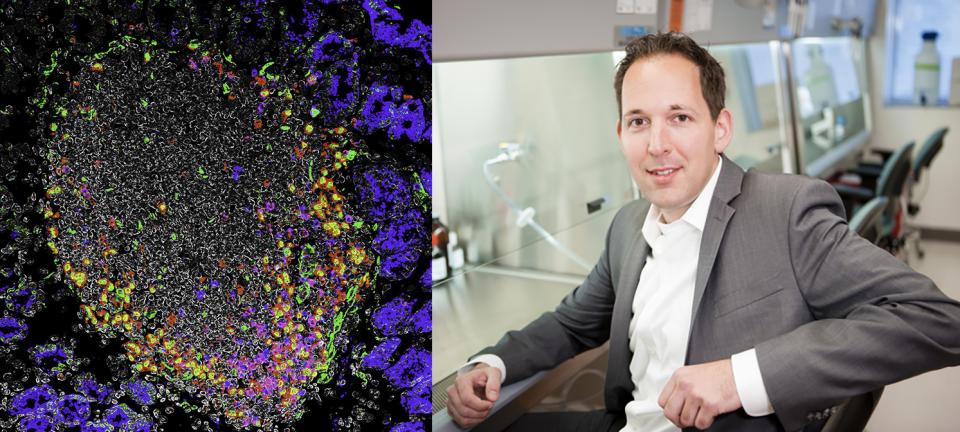

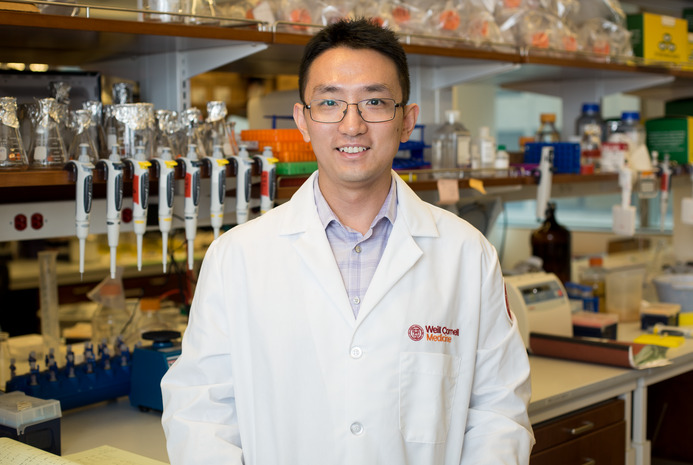

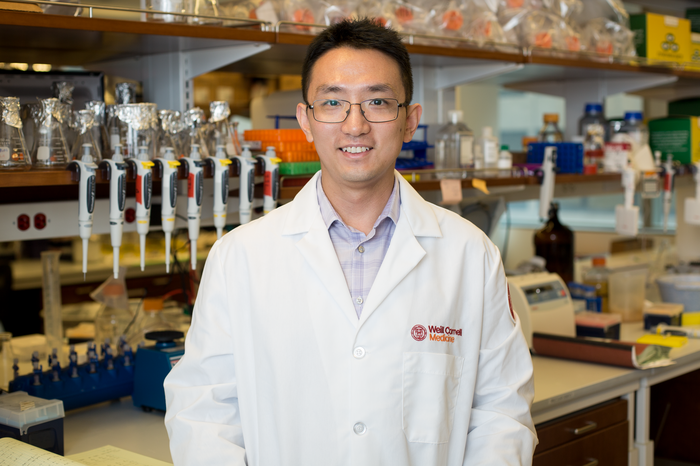

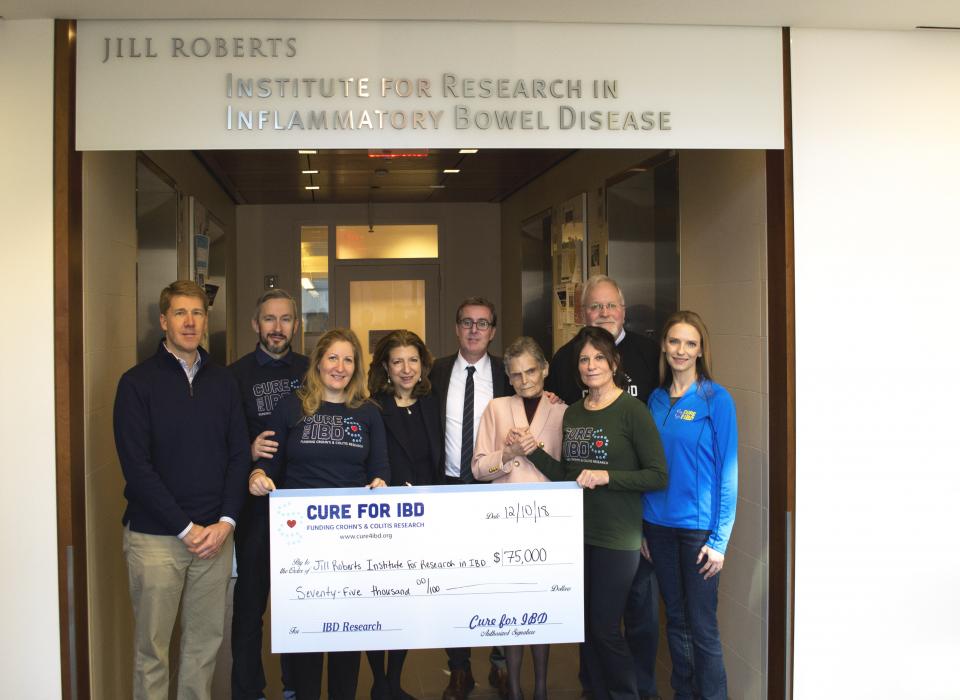

Dr. David Artis, director of the Jill Roberts Institute and the Michael Kors Professor in Immunology, along with Dr. Chun-Jun Guo, an associate professor of immunology in medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and a scientist at the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Dr. Frank Schroeder, a professor at the Boyce Thompson Institute and a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology in the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University, have been awarded the 2025 Biocodex International Microbiota Grant.

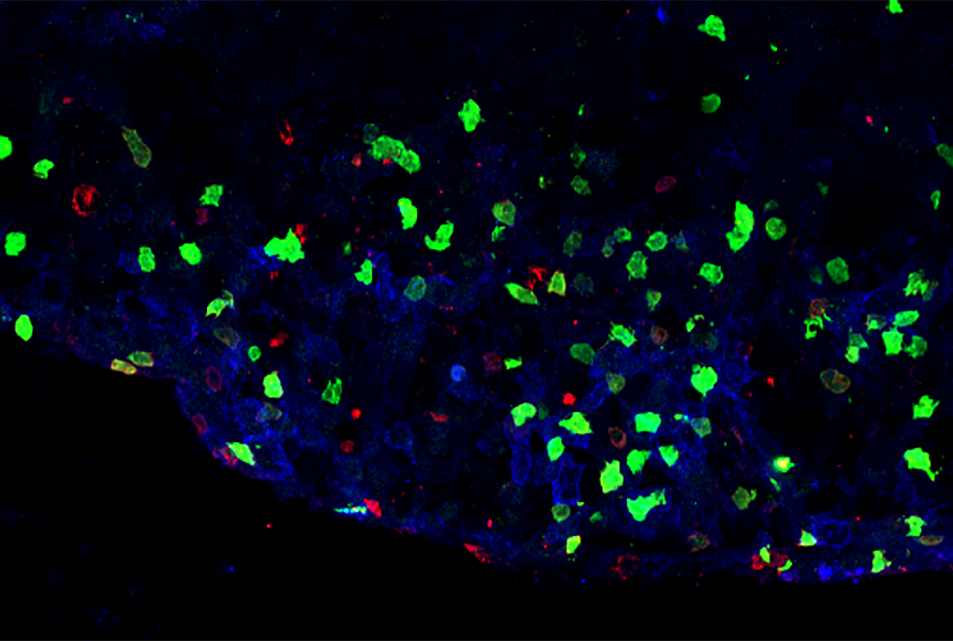

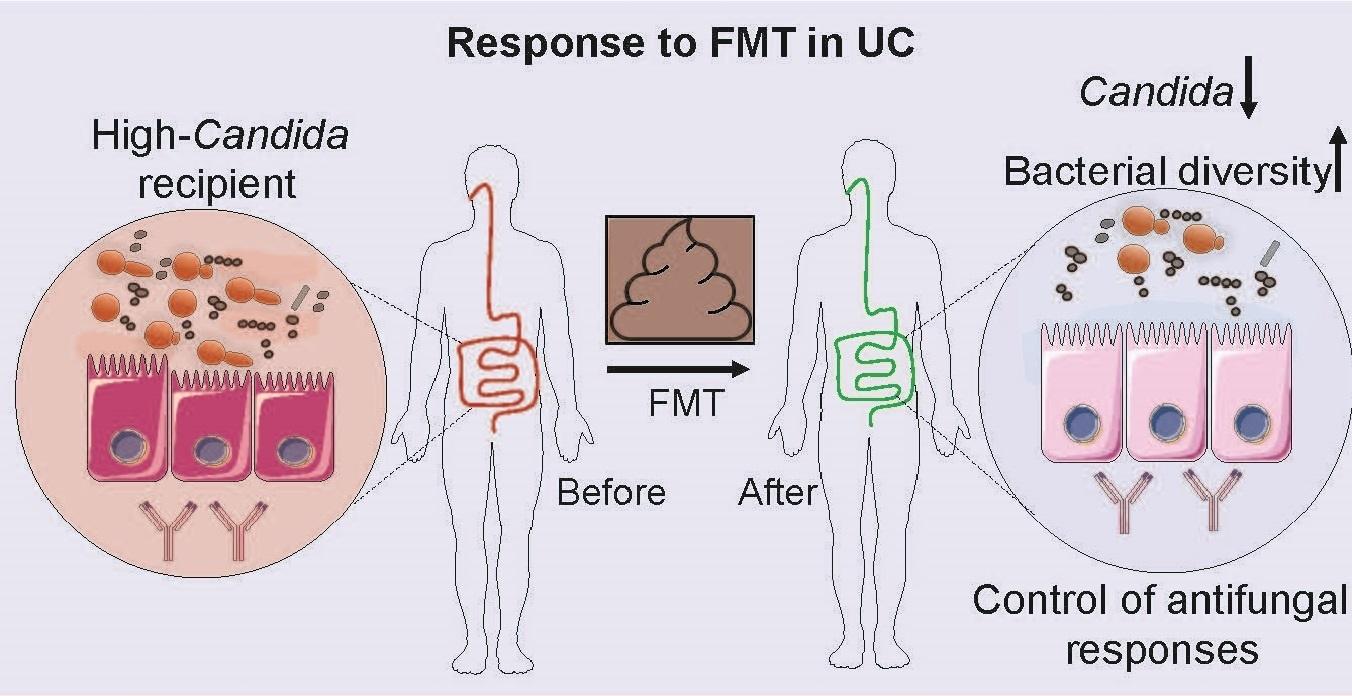

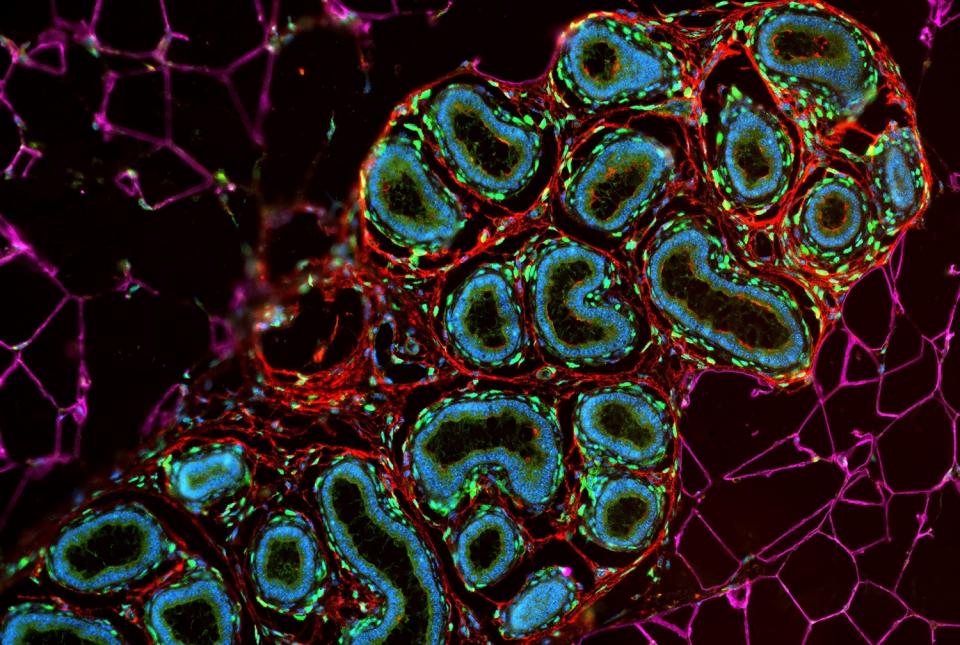

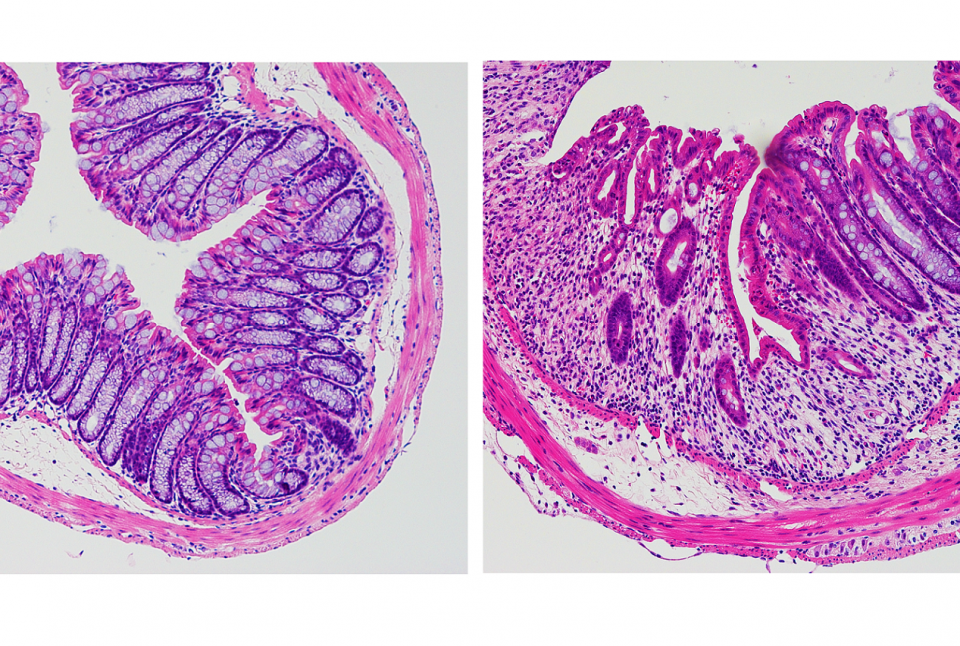

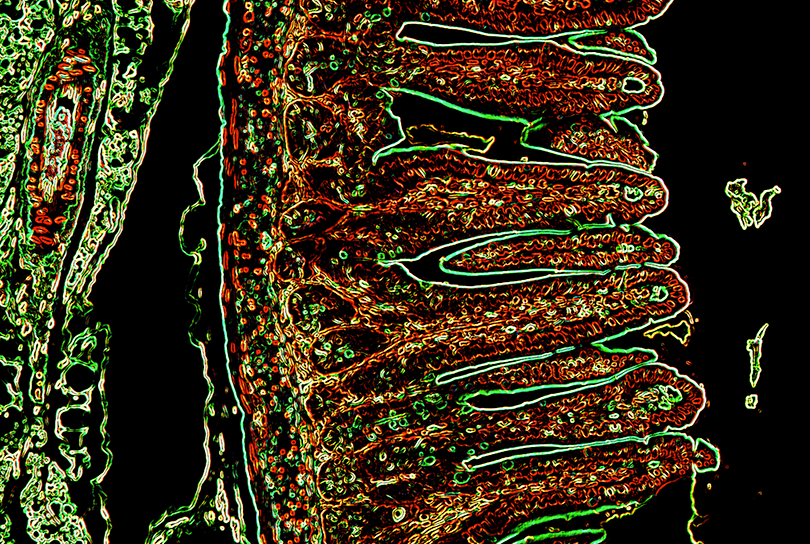

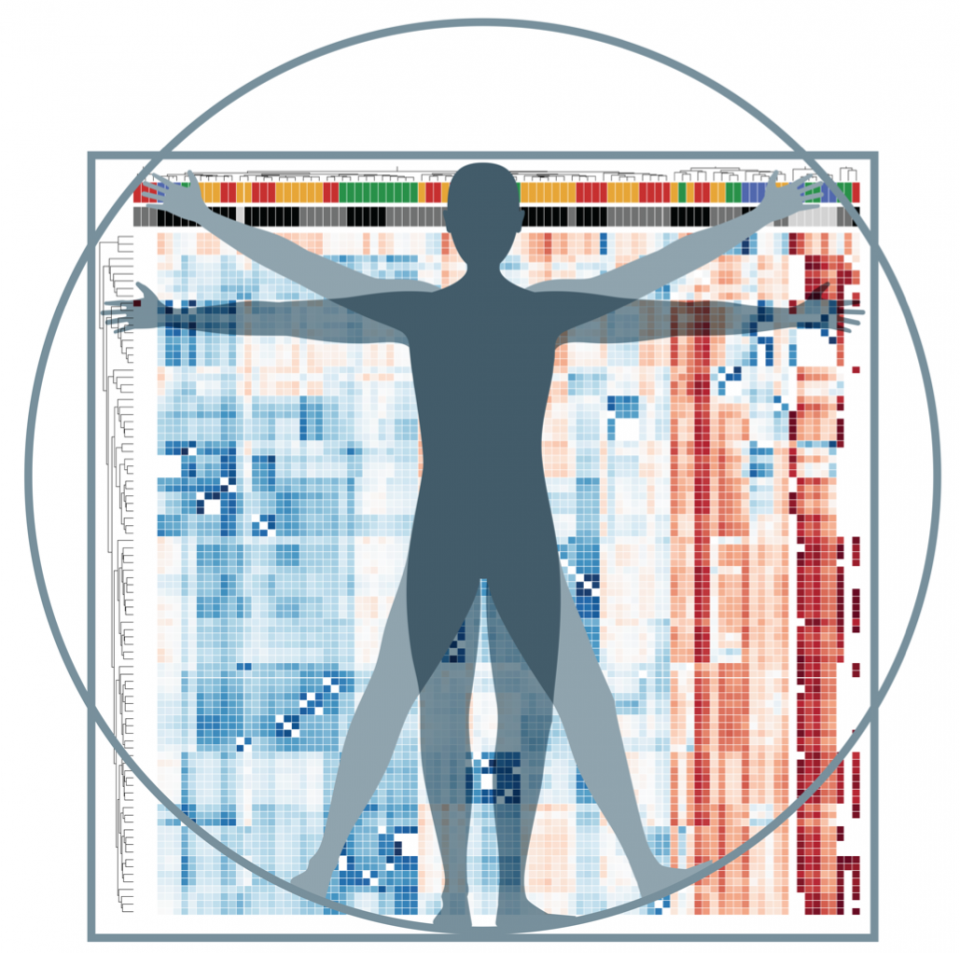

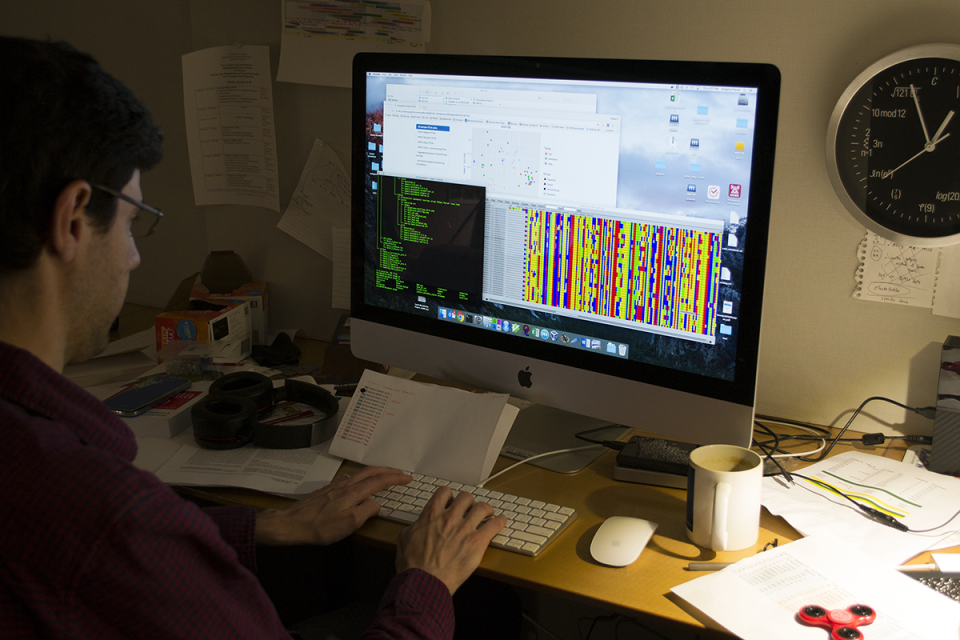

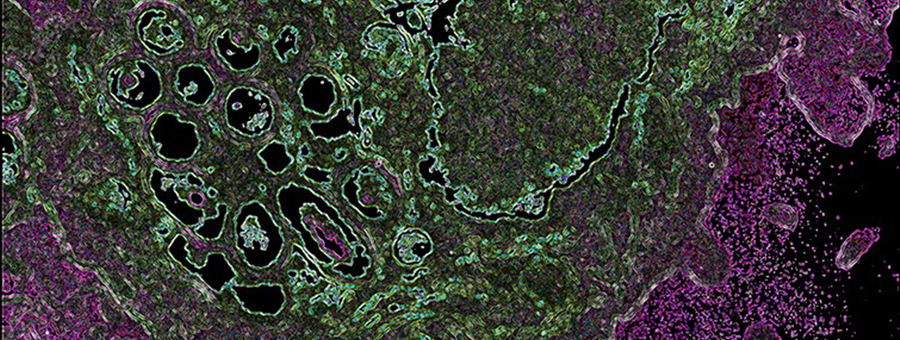

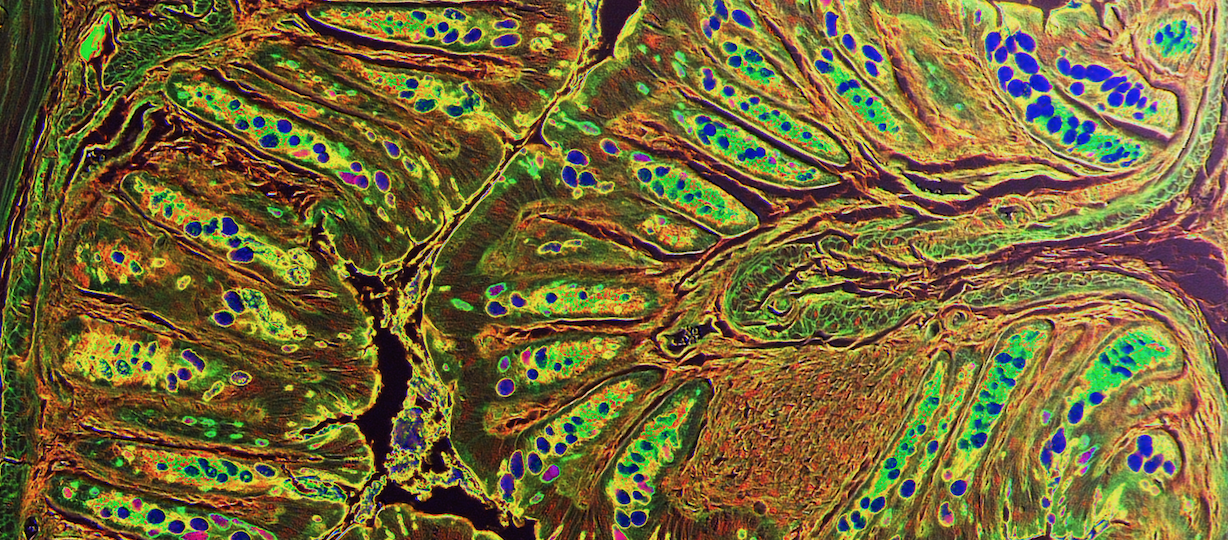

The grant supports a cross-campus collaboration between Weil Cornell Medicine and Cornell University in Ithaca. Together, with support from this grant, Drs. Artis, Guo, and Schroeder will spearhead a multidisciplinary initiative to deepen the understanding of how host-microbiota interactions shape human health and contribute to disease.

Biocodex, a global, family-owned pharmaceutical company, is recognized for its commitment to advancing gut microbiota science and developing innovative health solutions.

“This opportunity to partner with Biocodex allows us to begin to drill deeper to understand how this relationship between microbes and the human body is regulated and how we might harness that regulation and interaction for new therapies,” Dr. Artis said.

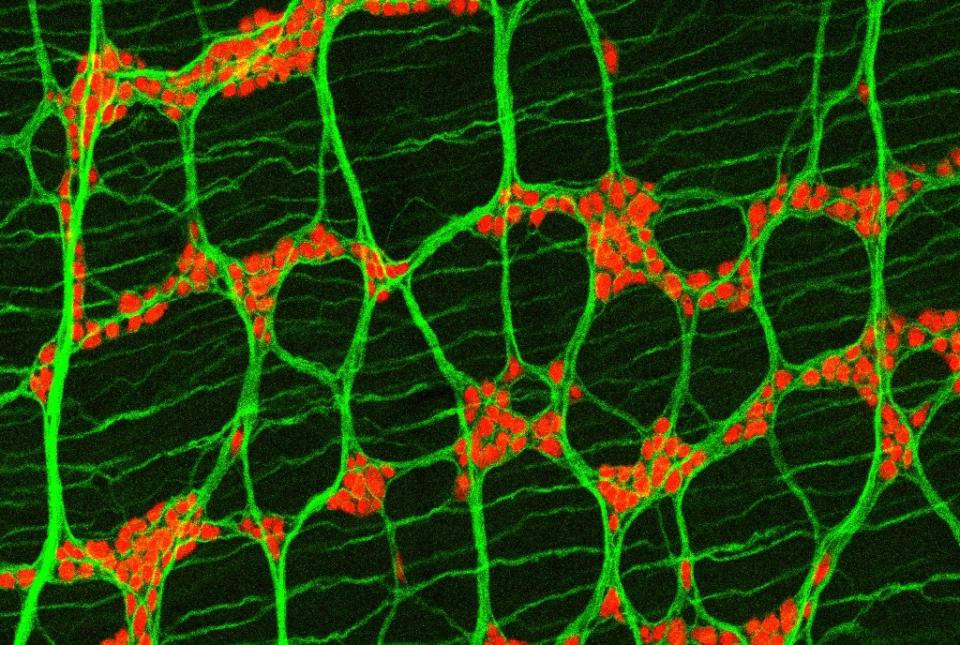

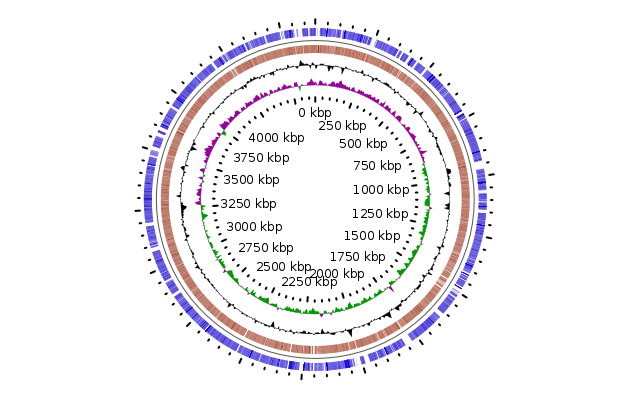

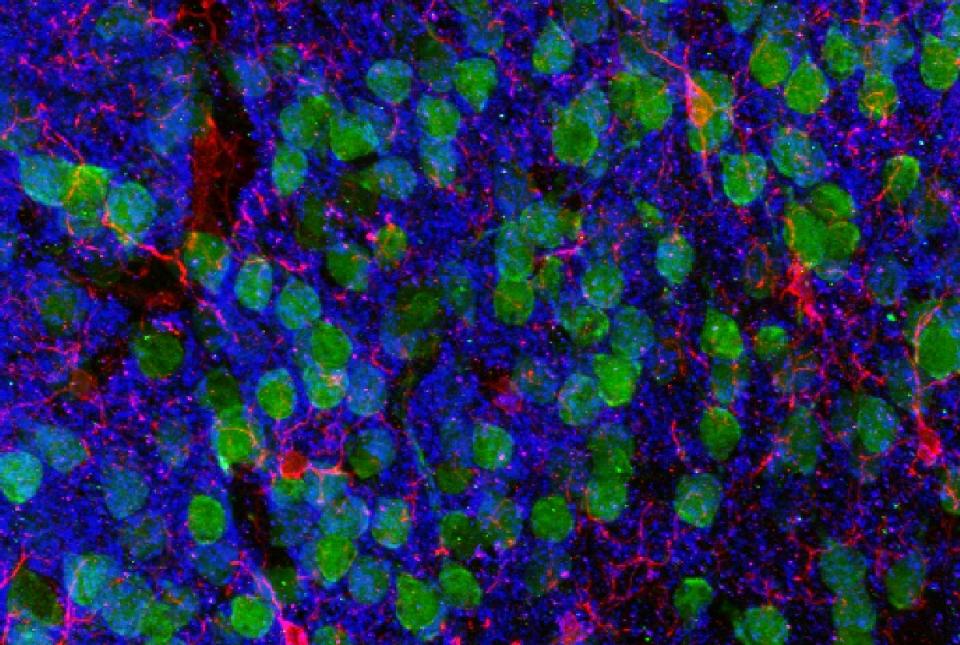

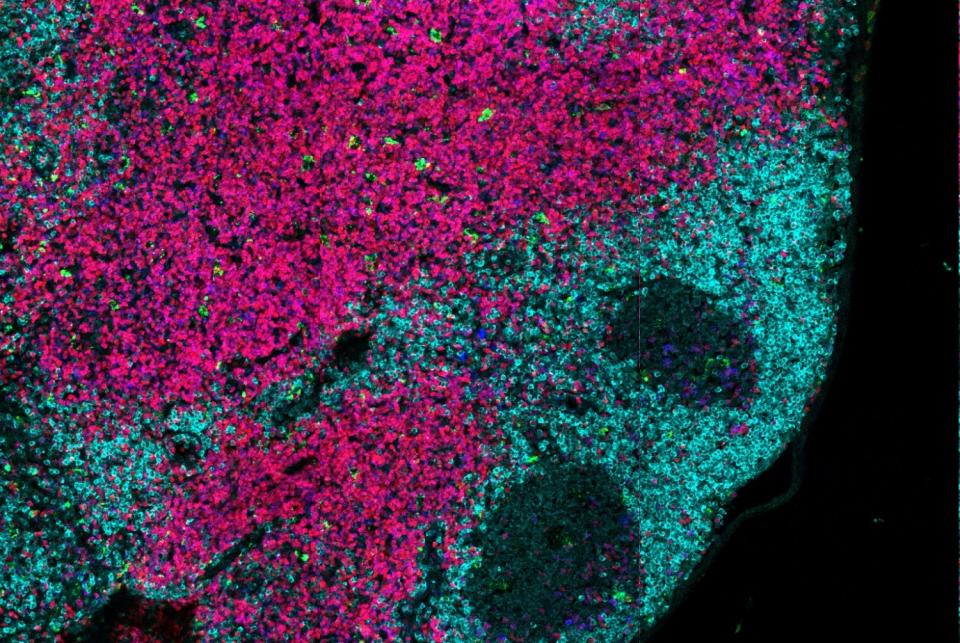

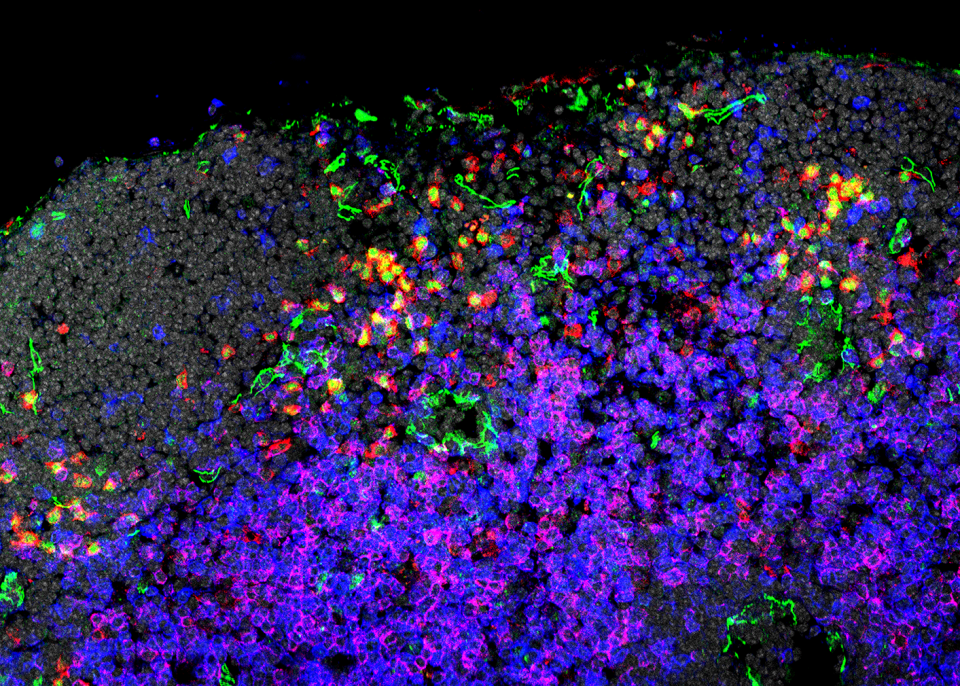

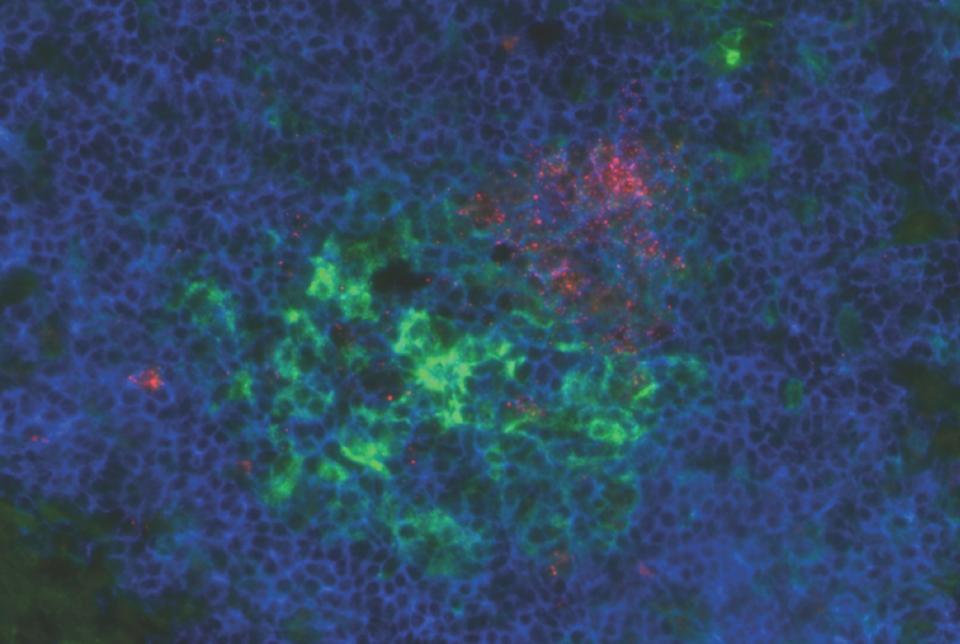

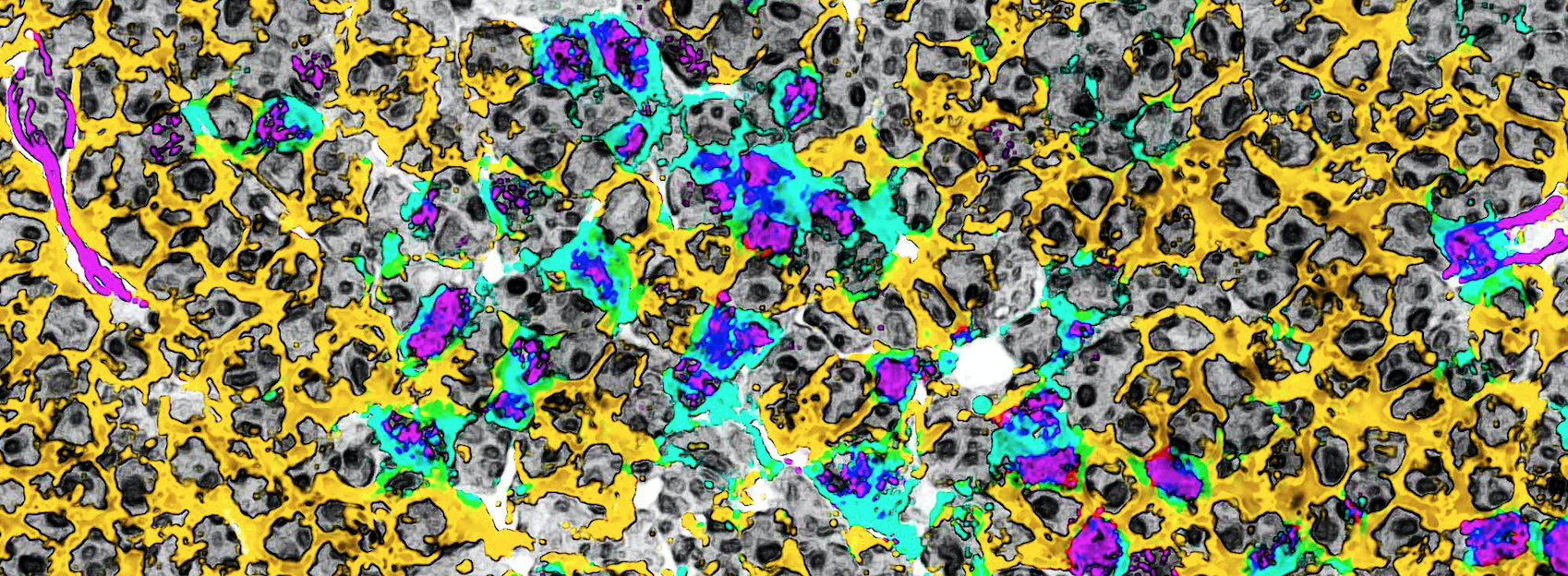

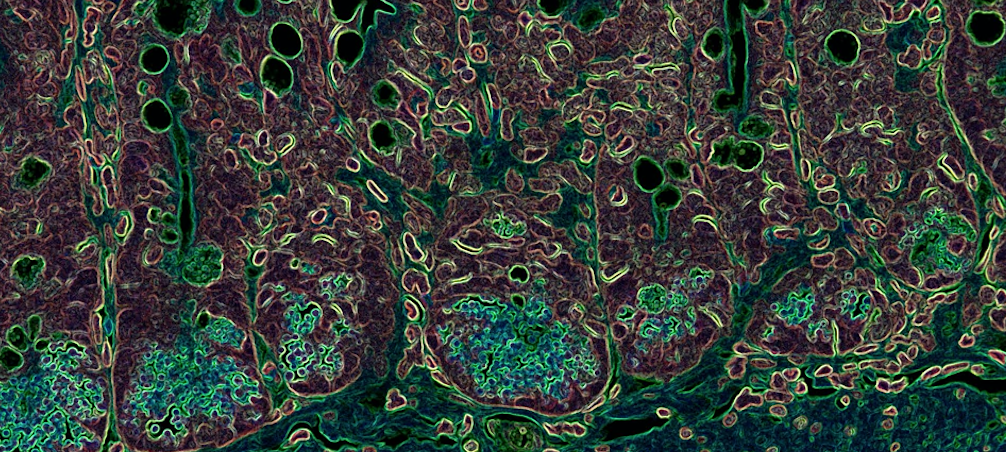

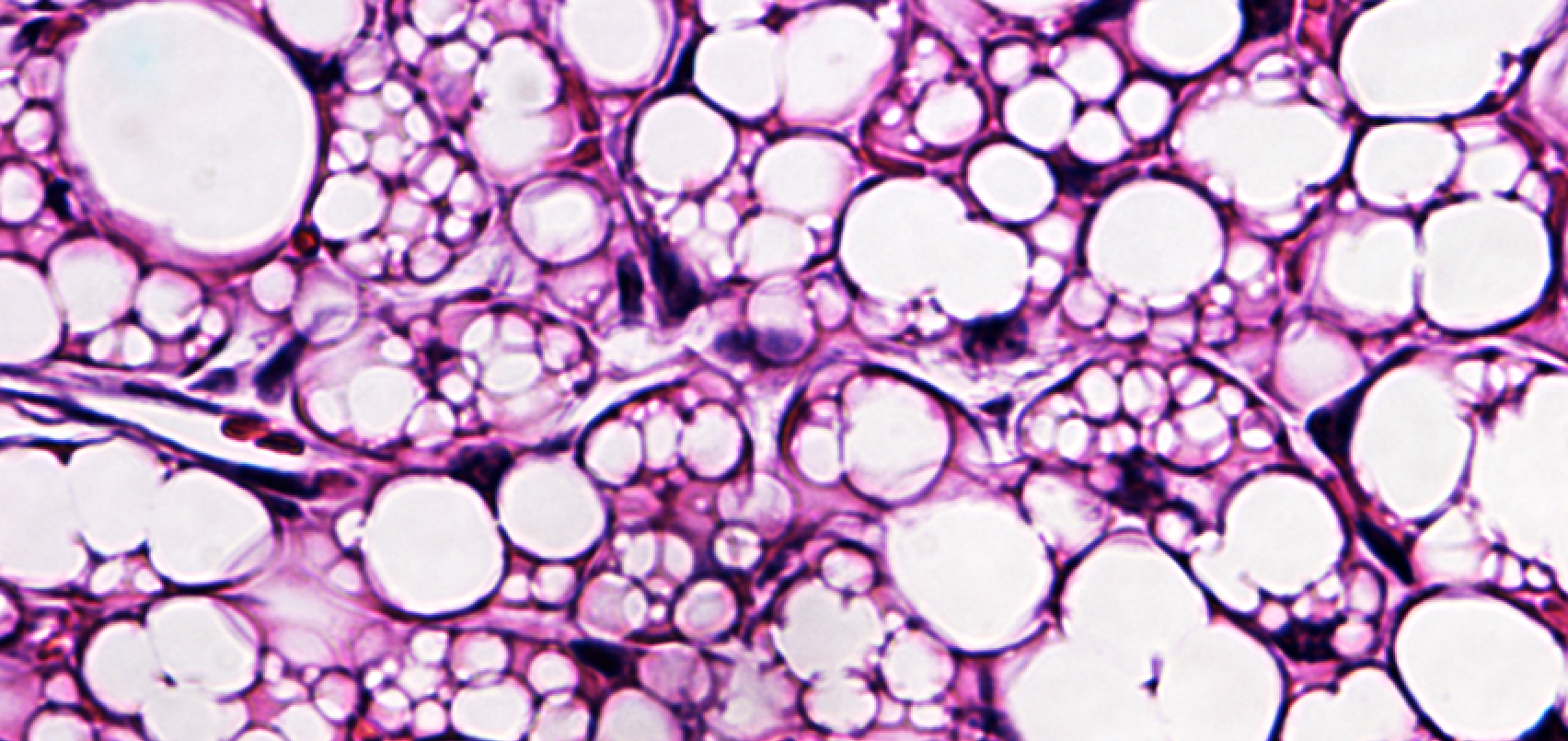

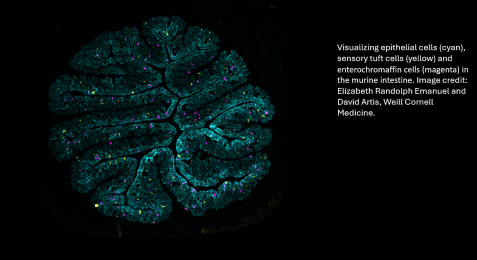

He said now that the immunology field recognizes how the composition of microbial communities changes the context of disease, the next challenge is to understand what is it that these microbes are making that is influencing the immune system, the metabolic system or the nervous system.

“The purpose of this grant is to focus on defining the molecules that are made by these microbes and how they are recognized by the human body and how we can intercept that interaction to influence the development of drugs—that’s the exciting, new prospect,” Dr. Artis said.

He also noted the unique value of this collaboration. “This grant affords us an opportunity to do a whole new set of studies that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. The opportunity to bring together a multidisciplinary team and collaborate with Cornell University in Ithaca to study this complex problem is a unique opportunity.”

Dr. Robert S. Brown, Jr., the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Medicine, clinical chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and medical director of the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at the NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine Medical Center, added “The ongoing collaborative work being done in the Jill Roberts Institute and the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology ensures that the latest scientific advances in our understanding of the gut microbiome and immune system can be tested and applied in our patients, leading to novel breakthroughs. The Biocodex grant is an exciting opportunity to leverage these discoveries toward the development of therapeutic interventions.”

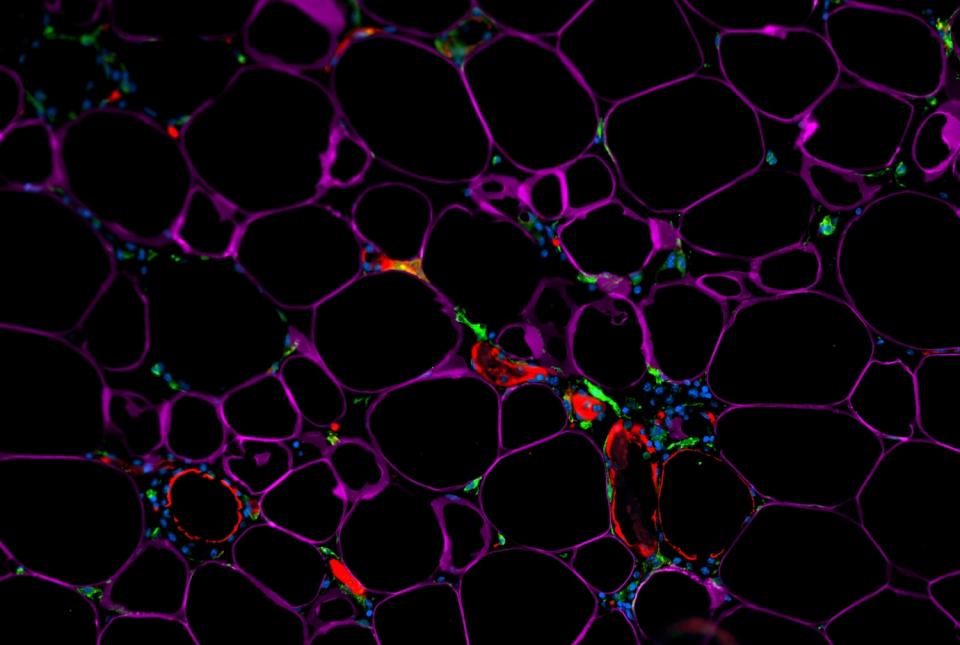

Dr. Artis said the long-term goal is to make innovative discoveries that will allow their team to build a pipeline of novel therapeutics for conditions such as metabolic disorders, obesity-related diseases, chronic inflammation, cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The team is also exploring the gut-brain axis to uncover new strategies for treating mental health conditions.

“The hope is that we’re going to identify molecules that are influencing these pathways that we can use as therapeutic targets, that is what’s most exciting,” Dr. Artis said.